|

| Moles! |

If you were in a high school chemistry class, you may remember learning about Avogadro's number, 6.02214X×1023, aka the mole. Because of this one number, the mole has been adopted as the official animal mascot of chemistry. Chemistry classes tend to celebrate Mole Day on October 23, which is still a few weeks away, but I decided that I would take a break from sewing pants muslins and try out some of the mole stuffed animal sewing patterns out there. Since I'm planning on giving away a couple of them to my top students, I need to get a head start! And teenagers still count as kids, right? And because this is about stashbusting, I used leftover bits of fleece and wool in my stash to make these little guys.

|

| Look, it's like he's an officiant conducting a marriage ceremony! All together now: awwww... |

There are two main mole sewing patterns out there: a simple one and a more advanced one. I remember my sister making the former when she was a chemistry student, but this is the first time I've made one myself in my eight years of teaching chemistry -- what a shame! I don't know how many people are interested in a review of such a niche sewing pattern, but in case anyone is interested, here are my thoughts:

|

| Look, it's giving the other one a massage! |

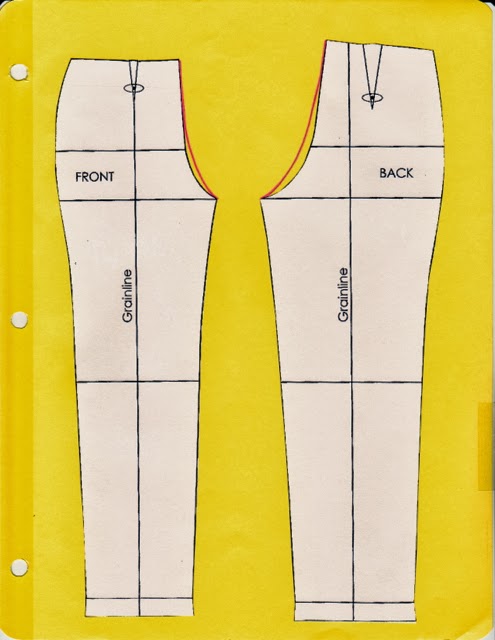

Simple Mole Pattern: This pattern is easy to sew even for someone with relatively little experience sewing, since it's made for students to do in class from felt and such. The resulting mole is smallish (7.5"x3" not including any tail one might add) but is easily recognizable as a mole. It is easier to add eyes before sewing the body pieces together, but there are no marks on the pattern for where to do so. I found the feet really fiddly to cut before sewing them to the body, and if they're not exactly the right size and placed just right, they get caught in the other seams and then turn out all warped when you flip the mole right side out. For my second mole I actually cut out tiny little rectangles and just cut the claws once I had sewn and flipped the mole body. I would've liked to have an actual tail pattern included and sewn the same way the paws are attached, instead of having it tacked on as an afterthought after it's all sewn up. Still, for the ease of sewing, you get a decent, recognizable animal.

|

| This guy is ready for a hug, but there's no one there for him to hug...sorry dude, but I don't feel like making you a pal. |

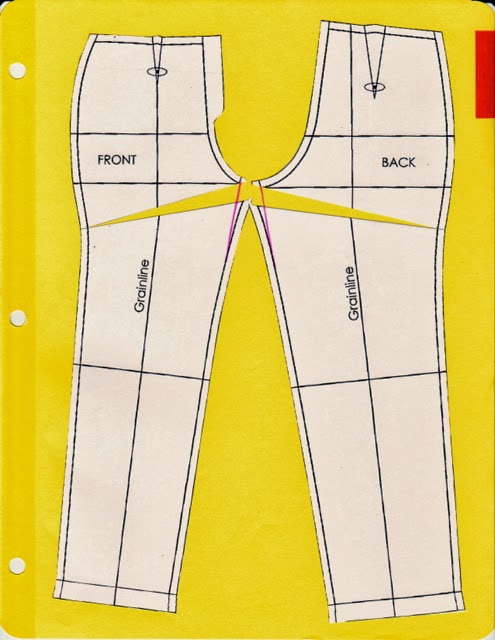

Advanced Mole Pattern: This pattern is definitely trickier, even for a sewist who's made plushies before. This pattern was designed to be able to sit up like a teddy bear, and the engineer in me really appreciates the thought that obviously went into the design (go check it out -- it's quite clever and probably adaptable for other similarly shaped animals). That said, I think the resulting mole actually looks less mole-like and more cartoon-like, which perhaps was the goal? I did really like the paw design and the cute little stub tail. It took me a little bit to figure out the odd directions (I'm too used to reading "official" sewing directions like "right sides together" and had to mentally adjust to "fur side in"), especially for sewing the neck area. If I were to make this pattern again, I'd actually change up the base/butt area to be wider than the top so that the mole would sit more stably.

|

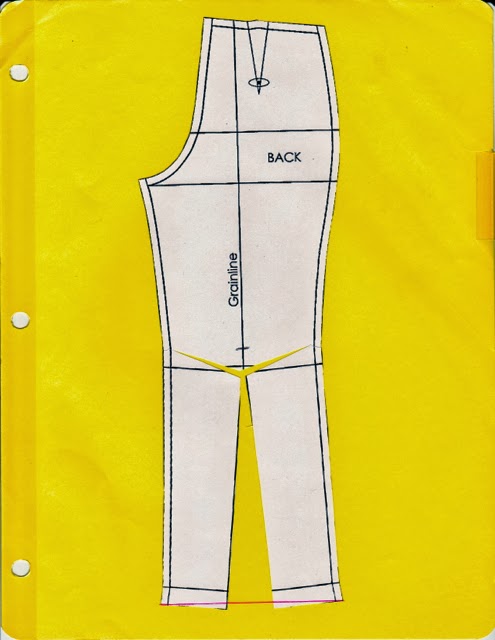

| Just to give you an idea of scale: here's Walnut posing reluctantly with the two matching moles. |

So there you have it -- start preparing early for Mole Day! And if you're not so inclined, you can always show off your other sewing-for-kids projects in the return of the link party...

October is sewing for others month, which means it's time for some